Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of digital dental impressions obtained by intraoral scanning (IOS) for partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects by comparing them with conventional impression techniques. Ten subjects underwent an experimental procedure where three ceramic blocks were affixed to the healthy palate mucosa. Digital dental impressions were captured using IOS and subsequently imported into software. Conventional impressions obtained by silicone rubber were also taken and scanned. Linear distance and best-fit algorithm measurements were performed using conventional impression techniques as the reference. Twenty impressions were analyzed, which included 30 pairs of linear distances and 10 best-fit algorithm measurements. Regarding linear distance, paired two-sample t-test demonstrated no significant differences between IOS and model scanning in groups A and C, whereas significant differences were found in group B (P < 0.05). Additionally, ANOVA revealed significant differences among the groups (P < 0.05). No significant differences were found for the best-fit algorithm measurement of the dentition. IOS can provide accurate impressions for partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects and its accuracy was found to be comparable with conventional impression techniques. A functional impression may be needed to ensure accurate reproduction of soft and hard tissues in defect or flap areas.

Introduction

Making dental impressions, which is usually considered to be the first step for dental procedures, is necessary in most clinical settings1. In clinical scenarios, conventional dental impressions obtained by alginate or silicone rubber were applied to measure the occlusal relationship and dentition. However, this method is associated with several drawbacks, including the significant time and cost involved in model fabrication, impression-taking, and model storage2. Furthermore, research has shown that conventional dental impressions are prone to inaccuracies due to factors such as potential distortion and expansion of gypsum casts, as well as changes in shape over time when impressions are sent to dental laboratories3,4,5. Digital dental impressions, which have been gradually applied in clinical practice, have emerged as a promising solution to the limitations of traditional dental impressions. Compared to conventional methods, digital dental impressions offer several advantages, such as real-time imaging and evaluation, less requirement for materials, and improved cost-effectiveness and communication6. Studies have shown that their accuracy can be acceptable in clinical settings compared with conventional ones7,8,9,10.

In general, digital dental impressions can be acquired either by scanning the conventional impressions or by IOS with an intraoral scanner. The accuracy of dental extraoral laboratory scanners has been evaluated in previous studies11,12. Data acquired using IOS is comparable to that obtained using conventional methods for single crowns and partial fixed prostheses13,14. Nevertheless, researchers have reported that extraoral scanners demonstrated higher accuracy measurements for the cross-arch measurement15. In addition, studies have found that prosthesis fabricated from model scanning has lower average discrepancies than those produced using IOS16.

Maxillary tumors can result in significant loss of hard and soft tissues, leading to maxillary defects and decreased quality of life for patients. Therefore, treatment of the maxillary defects should focus on minimizing potential problems and preserving quality of life. The fabrication of a maxillary obturator can help to address these issues, and reports have shown that patients experience improved satisfaction with the use of a maxillary obturator17,18. For partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects, conventional dental impressions using silicone rubber or alginate are still widely used in clinical practice due to their acceptable accuracy and feasibility19,20. Nonetheless, these patients may experience difficulties with mouth opening due to scar contracture or temporomandibular joint disease, which can impact the accuracy and feasibility of conventional dental impressions. Moreover, defective tissues of the upper palate and the penetration between the oral cavity and nasal cavity may cause materials to enter the nasopharynx cavity, bringing pain and discomfort to patients. Accordingly, making dental impressions for this specific clinical population, partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects, could be an enormous challenge for dentists during the clinical practice of dentistry.

With the rapid advancement of digital technology in dentistry, practitioners can now obtain 3D scans of hard and soft tissues and occlusion relationships using intraoral scanners. This method eliminates the drawbacks of conventional dental impressions and enables practitioners to digitally evaluate and design the maxillary obturator. Compared to conventional impression techniques, the use of IOS simplifies the workflow and avoids time consumption and potential deviations21. Trueness, which describes the congruence between a prototype STL dataset and a control STL dataset, is considered a crucial factor in determining the ability of IOS to capture dental impressions with high quality22,23.

The accuracy of IOS has been reported to decrease when scanning larger areas compared with a short span24,25. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the accuracy of digital dental impressions obtained from IOS for partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects by comparing the linear distance and best-fit algorithm measurements with those obtained from conventional impression techniques in a quantitative manner.

Materials and methods

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fujian, PR CHINA (No. MRCTA, ECFAH of FMU [2020] 430). Written informed consents were obtained from ten partial edentulous patients with maxillary defects in full accordance with the ethical principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (version 2008). The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) mild to moderate limitation of mouth opening; (3) inability or refusal to undergo implant surgery due to physical conditions, but required prosthetic restoration. The excursion criteria were (1) severe mouth opening limitation; (2) tooth mobility > I.

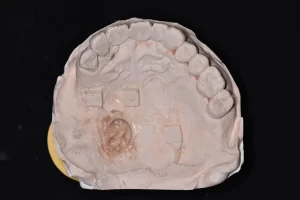

Placement of ceramic blocks

Before the experiment, the dentition and mucosa of the subjects were isolated and dried using an air syringe, and cottons. To protect the mucosa of the defect areas, vaseline gauze was used. Three customized zirconia ceramic blocks (6 mm × 6 mm × 3 mm) were attached to the healthy palate mucosa of residual dentition and the defect area using medical tissue glue (Medical Tissue Glue, B. Braun Corp, China). The ceramic block at the anterior position of the residual dentition was marked as A block, the block placed near the defect area or flap area was labeled as B block, and the ceramic block at the posterior of the residual dentition was marked as C block.

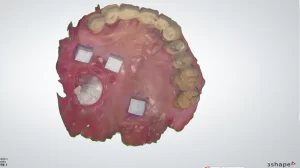

Intraoral scanning

Each patient received both conventional impression-taking and IOS. The digital dental impression of IOS was before the conventional impression techniques procedure. Digital dental impressions were obtained using an intraoral scanner (TRIOS color, 3Shape, Denmark) by an experienced dentist. Starting from the occlusal-palatal side of posterior teeth in the first quadrant, the intraoral scanner was turned to the buccal side of the teeth in the second quadrant and then returned to the first quadrant. The mucosa of each patient was also scanned, and the scan data was saved and exported in the STL format.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Conventional impression techniques

For each participant, maxillary silicone rubber impressions (Meijiayin elastomer impression material type III, HuGe, China) were taken using full-arch metal stock impression trays in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions under the same conditions. The dental impressions were then poured with dental stone (Die-stone, Heraeus Kulzer, USA) by the same experienced dentist. After 40 min, impression trays were removed from the stone models. The stone models were then scanned by using a desktop scanner (E2 lab scanner, 3shape, Denmark) and saved in STL format.

Figure 3